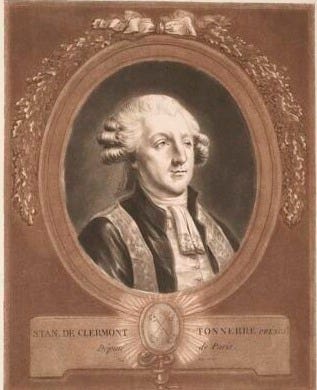

A salutary reminder from de Clermont‑Tonnerre

While ethnic essentialism and tribalism are flourishing, revisiting Stanislas de Clermont‑Tonnerre’s speech of December 23 , 1789 serves as a reminder to what the Republic is.

For nearly a decade now, Yaël Braun‑Pivet has been a source of embarrassment rather than admiration. A trained attorney who won a seat in the Frech National Assembly1 in 2017 thanks to La République En Marche!’s (Emmanuel Macron then “political party”, since then redubbed “Renaissance”) aggressive “CV‑driven” recruitment, she has already drawn criticism for a naïve inquiry: reportedly asking a senior official at the National Assembly, “When are the decrees actually voted on?”.

Braun‑Pivet secured a second term as Speaker of the House by means of a circuitous maneuver that many observers label as typical “Macron‑style” tactics. Ministers of an outsted gouvernment re‑entered parliamentary life and effectively tipped the scales in favor of Braun‑Pivet, while they were still ministers of a government in care-taker mode.

The French Constitution explicitly bars members of the executive from holding a seat in the legislature at the same time—a safeguard designed to preserve the separation of powers. The episode has only deepened doubts about Braun-Pivets credibility, leaving her with a thin veneer of legitimacy in the wider public.

On what grounds does the Speaker of the French National Assembly address “as a Jew” a foreign head of state—specifically, the President of the Palestinian Authority— ? In her role as the representative of a part the parliamentary branch, she is bound by an absolute duty of neutrality.

The intolerable “dictatorship of minorities” that has taken root in France—some will argue that both the left and the right have actively fostered it in order to cultivate neatly segmented constituencies that are easier to manage than the chaotic masses—is fundamentally tribal and rooted in ethnic or communal essentialism.

Zionism, Islamism, and societal communitarianism are all forms of separatism. They share rooted in a victimhood narrative that is designed to grant members of these groups a moral and social advantage, special privileges, and a degree of immunity that does not extend to the majority - as well as an unimpeachable licence to double standards.

And let no one bring up the term ‘Shoah,’ which fails to accurately describe the planned, industrial extermination of Europeans by other Europeans because they were Jewish, homosexuals, Gispies, psychiatric paitents etc. Nazism amounted to a total, holistic negation of Western civilization, which—let us remember—is rooted in Christianity. As André Malraux put it, ‘A civilization is defined by what forms around its religion.’ In the Christian tradition, collective punishment does not exist; God alone judges each person individually. Isn’t that the very basis of our criminal justice system? No decimation2. Whether one is a beleiver or not: that’s what and who we are.

The question of minorities surfaced almost immediately after the 1789 French revolution, alongside the issue of discrimination.

The Republic is universal, and French nationalism is likewise universal—unlike British, German, Scandinavian, Polish, Baltic, Arab nationalisms, or Zionism, which are particularist ethno‑nationalisms. Our universalist nationalism makes us, French, the Europeans most akin to Americans.

From the earliest months of the Republic, a set of principles was articulated that remain valid today. This is what Stanislas de Clermont‑Tonnerre emphasized on December, the 23rd of 1789. He laid down the foundations of belonging to the French Nation, a belonging that excludes no one who voluntarily embraces its principles.

His thesis is straightforward: no distinct nation may be formed within the French nation. To allow that would suffocate the volonté générale—the will of the people—and thus undermine sovereignty. Whenever a nation other than the French nation, or a community other than the national community, influences legislation, the will ceases to be that of the people, who cease to be free.

De Clermont-Tonnerre’s reflections are worth pondering, not only with regards to sectarian separatism but also in relation to the European Union.

Session of Wednesday, 23 December 1789 of the National Assembly

“You have already secured the rights of man and citizen through the Declaration of Rights3; and afterwards you irrevocably established the qualifications required for eligibility to administrative bodies. It seemed that nothing more remained to be done on that subject. Yet one honourable member rose to inform us that non-Catholic inhabitants of several provinces find their rights violated on the basis of statutes applied specifically to them. Another drew your attention to citizens who face professional barriers that prevent them from enjoying the same rights as others. I proposed a motion whose purpose was not to broaden the eligibility clauses. Thus I have two issues to examine: exclusion based on profession, and exclusion based on religious belief.

Professions are either harmful or they are not. If they are harmful, they constitute an offence that justice must punish. If they are not, the law must conform to Justice, which is the very source of law. The law should work to correct abuses, not to fell the tree that merely needs straightening or grafting. Among these professions there are two that seem difficult to mention side by side; yet for legislators, nothing should be separated except good from evil. I speak of the executors of criminal sentences,4 and of those who perform in our theatres5.

Concerning the first profession, I observe that the prejudice against it is shallow and rooted in outdated norms; we must change those norms in order to eradicate the prejudice. In military practice, when a person is sentenced to death or to some punishment, the hand that executes the sentence is not dishonoured. Whatever the law commands is legitimate; it commands the death of a criminal, and the executor merely obeys the law. It is absurd for the law to say to a man, “Do this, and if you do, you shall be stained with infamy.”

Let me now turn to theatrical actors. The prejudice against them comes from their dependence on public opinion. Yet that very dependence is our glory—and supposedly it debases them! Honourable citizens can bring to the stage the masterpieces of the human mind, works filled with sound philosophy that, placed within everyone’s reach, helped prepare the very revolution now underway. And you would say to them: “You are the king’s actors, you stand upon the nation’s stage, and you are infamous!” The law must not allow such disgrace to persist. If theatrical performances, instead of being schools of virtue, encourage vice, then purify them, elevate them—do not degrade the people who exercise admirable talents. And when you ask, “Do you propose to let actors be elected to judicial functions or to the National Assembly?” I say: I wish them to be eligible if they deserve it. I defer to the people’s choice, and I am not troubled; I do not wish to demean anyone, nor to outlaw professions that the law has never prohibited.

Now let me address religion. You have already spoken on this matter by declaring, in the Declaration of Rights, that no one shall be troubled for his opinions, even religious ones. Is it not fundamentally an injustice to deprive citizens of their most precious rights because of their beliefs? The law has no power over a person’s worship; it cannot reach the soul—it can only regulate outward actions, and it must protect those actions when they do no harm to society. God willed that we should agree on morality, and allowed us to enact moral laws; but He reserved for Himself alone the domain of doctrine and the empire of conscience. Leave consciences free: let feeling and thought, directed heavenward in whatever manner, not be turned into crimes punished by the loss of civil rights. Otherwise, forge a national religion, arm it with a sword, and tear up your Declaration of Rights. This is justice; this is reason—now consider also political prudence.

Every religion need answer for only one thing: its morality. If a religion orders theft or arson, then indeed its adherents should not only be barred from public offices but proscribed altogether. But this accusation cannot be applied to the Jews. Many charges are brought against them. The most serious are unjust; the rest are no more than minor offences. People say that usury is permitted to them: this claim is based on a false interpretation of a principle of beneficence and brotherhood, one that merely forbids them from lending at interest among themselves. Men who possess nothing but money must live by putting that money to use—and you have always prevented them from possessing anything else6. They are said to be unsociable; that alleged unsociability is far from proven.

Everything must be denied to the Jews as a nation; everything must be granted to them as individuals. They must be citizens. It is said that they do not wish to be so. If it’s true, let them declare it—and let them be banished! There can be no nation within the nation. The emperor admitted the Jews to all dignities, to all offices. They have exercised the highest public functions in France. One of our colleagues, Mr. Nérac, authorised me to say that several Jews took part in his election. They are admitted to the military corps: when I presided, a patriotic donation was presented to me by a Jewish soldier—a national guardsman.

The Jews are presumed citizens unless proved otherwise, unless they refuse citizenship. In their petition they ask to be regarded as citizens; the law must recognise a title denied to them by prejudice alone. And yet it is said that the law has no power over prejudice. That was true when law was the work of a single man; when it is the work of all, it is no longer true.

We must clarify their status openly. Silence would be the worst of evils; it would mean seeing the good and refusing to pursue it; knowing the truth but not daring to speak it; and finally placing prejudice and law, error and reason upon the same throne.”

Stanilas de Clermont-Tonnerre

What has applied to the Jews since 1789 applies equally today to Muslims and to any other minority.

If we were to banish all those who have shown—through repeated behaviour and proven actions—that they refuse to be French citizens, we would solve a major problem, beginning with the importation of conflicts that are not ours.

This is, moreover, precisely what French law — Article 23-7 of the Civil Code — provides: ‘A French national who in fact behaves as the national of a foreign country may, if he holds that country’s nationality, be declared by decree, after a conforming opinion from the Council of State7, to have lost the status of French citizen.’

The House. In France, there’s a Senate too. Bicameral system.

Decimation was a punishment in the Roman legions, whereby one out of ten soldiers was executed randomly, regardless of his actual deeds.

The Declaration of Human Rights and of the Citizen was voted and enacted by the French National Assembly on August, 26, 1789.

Executionners were long ostracized in French society.

Theatrical actors were considered by the Catholic Church as heretics and excommunicated.

Before 1789, Jews were prohibited to own land or be part of guilds, i.e craft and professions.

France’s highest administrative court