Habemus Fraudam

Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Pope Francis, has shown less interest in the Church and the papacy than in the wielding of power. He was the Davos-Obama pope. The mainstream medias are ecstatic.

The passing of Pope Francis triggered an instant media canonization. Woe to those who would dare play the devil’s advocate! Since at L’Éclaireur we’re all graduates of the Gregorian University’s department of Satanism (that’s ironic), we take on the task without the slightest fear of God. Isn’t he love and forgiveness?

The political and media elites have launched into rhetorical competitions, lauding a pontificate supposedly defined by profound humanity and advocacy for the vulnerable, particularly migrants.

We beg to differ. Declaring that the poor and the disenfranchised cannot work towards their own salvation is far from groundbreaking—it’s a regressive stance. It echoes the paternalistic sermons of 19th-century Catholic progressives, designed to preserve the social hierarchy.

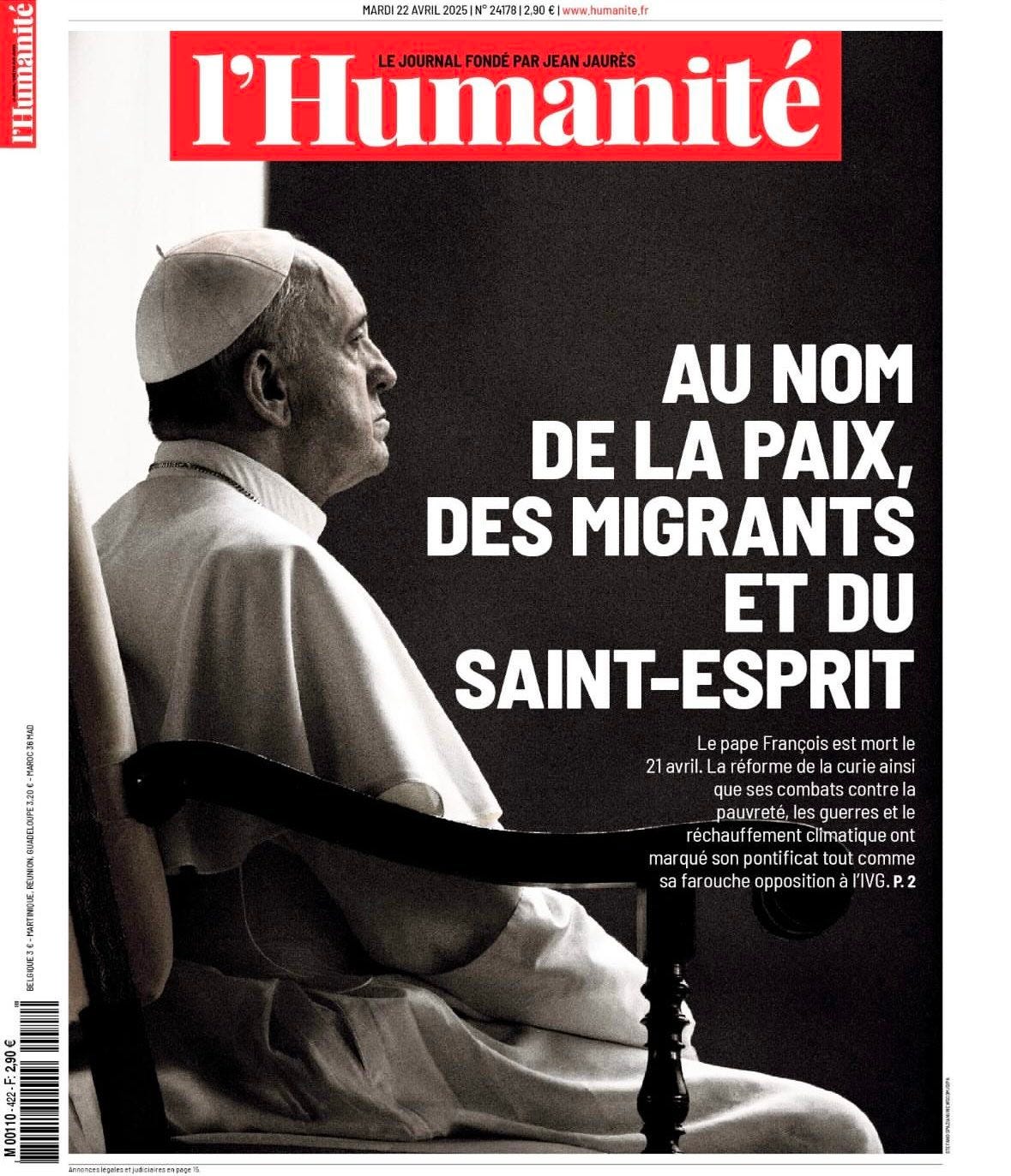

L’Humanité1 attributes the Curia’s reform to Francis. In truth, it was Joseph Ratzinger, Benedict XVI—the only pope since John XXIII with the intellectual and spiritual caliber for the papacy—who set it in motion by abdicating, a move that, unlike the death of a pope, dissolves the Curia. The Vatican’s entrenched corruption was otherwise untouchable.

Enamored with their selective narratives and performative empathy, Bergoglio’s laudators—across the political spectrum—conveniently erase inconvenient truths to fit their agendas.

A pope is, first and foremost, a human being and a politician. Jorge Mario Bergoglio, a Jesuit, embodied this, his cynicism so pronounced that some even label him criminal.

It’s ironic to witness the left lionize a figure who played a key role in stifling liberation theology in Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s. As Argentina’s Jesuit provincial, Bergoglio stood idly by while his subordinates were abducted and tortured by the military junta. Nor did he ever publicly condemn the atrocities of South American dictatorships, including Argentina’s own, despite their notoriety. Even less discussed is his membership, starting in the late 1960s, in the Peronist outfit Organización Única del Trasvasamiento Generacional.

Liberation theology sought to revive the Catholic Church’s foundational principles, advocating an internal reform—swiftly branded as Marxist (or populist in today’s terms)— that argued that beyond individual sin, there exists a collective sin rooted in social and economic systems inflicting mass suffering. It urged believers to form their own congregations and potentially elect their bishops, as in early Christianity, thereby defying the Pope’s authority.

Some could claim that Jorge Mario Bergoglio, akin to French Cardinal Alfred Baudrillart under Nazi occupation, yielded to his distaste for communism and his love for order. In the Cold War’s context, this might be seen as a grave sin but not unforgivable. Yet sin differs from crime, and this matter lies in the realm of politics, not faith.

Thus turning to politics, the papacy has historically harbored contempt for its eldest daughter, France, and for Poland, another primature. The Vatican’s enduring nostalgia for the Holy Roman Empire has tied it to its successors—initially the Austro-Hungarian Empire, then the German Reich, including its Third iteration.

This attachment underpinned the Vatican’s disturbingly lenient stance toward Nazism, a leniency that extended far beyond the war. The Vatican played a key role in orchestrating the escape of thousands of Nazi war criminals to South America and the Middle East while aiding in the transfer and concealment of a substantial portion of the Nazis’ infamous treasure, plundered throughout Europe. This loot fueled Germany’s postwar politics (political party funding) and its industrial revival.

For further insight, consider the remarkable documentary Le Système Octogon directed by Jean-Michel Meurice, built on the investigative work of Franck Garbely and the late Fabrizio Calvi. From 2008 to 2011, Germany persistently strived to block its airing on Arte, the French-German TV channel that had financed the project.

The exfiltration operations of Nazis and funds were largely driven by American operatives, notably Allen Dulles and James Jesus Angleton, both later pivotal in the CIA’s formation. Angleton, a devout catholic who started as the OSS Rome station chief in 1944, held exclusive control over U.S. intelligence ties with the Vatican (and Israel) until his dismissal in 1974. A significant and hardly trivial detail is the affiliation of many high-ranking U.S. intelligence and national security officials with Opus Dei, including the iconic William Colby, a lifelong intelligence officer and CIA director from 1973 to 1976.

The deep relationship between the Vatican and the United States, forged since the close of World War I, is telling. Initially driven by financial needs, the Catholic Church—asset-rich but cash-poor—began borrowing in the late 19th century, first from the Rothschilds. After the Vatican State was formalized by the 1929 Lateran Accords, negociating loans state-to-state became more straightforward, albeit through banks. With the United States as the world’s dominant financial power, this connection grew pivotal.

It’s hardly shocking that the shadowy Operation Gladio, a Cold War initiative, was bankrolled through the Vatican’s secretive financial networks, much like numerous covert CIA operations.

Equally unsurprising is the fact that the Vatican Bank, officially the Institute for the Works of Religion (IOR), was led from 1972 to 1989 by American Cardinal Paul Marcinkus, once an interpreter for John XXIII and a bodyguard for Paul VI, who kept a .357 Magnum tucked beneath his cassock. He reportedly stated “You can't run the Church on Hail Marys”.

A member of the infamous Propaganda Due (P2) Masonic lodge and known for his penchant for young women, Marcinkus implicated the Holy See in the largest money-laundering scandal ever exposed, in collusion with Michele Sindona, the mafia’s banker and a CIA asset, and Roberto Calvi, head of Banco Ambrosiano2. Sindona was killed in prison with cyanide-laced coffee, and Calvi was found hanged beneath a London bridge. Marcinkus, eventually sidelined by John Paul II after considerable effort, retired to a leisurely life of golf in Sun City, Arizona, where he lived until his death in 2006.

David Yallop, a foremost authority on the Vatican’s shadowy dealings, asserts that the death of John Paul I, a mere 33 days into his papacy, was a murder plotted by Paul Marcinkus, cardinals Villot and Cody, Roberto Calvi, and Licio Gelli, the grand master of the Propaganda Due (P2) lodge. John Paul I had reportedly planned to overhaul the Vatican’s corrupt financial system by turning over evidence of crimes involving the IOR, its affiliated banks, and P2 to Italian prosecutors.

He was succeeded by Karol Józef Wojtyła, John Paul II, selected largely for his fervent anti-communist stance. His election hinged on the steadfast backing of Austrian Cardinal Franz König, a progressive with astonishingly enough deep ties to Opus Dei, for which he ordained some hundred priests in Spain during the 1970s, including José Horacio Gómez, now Archbishop of Los Angeles and head of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, defying Pope Francis, approved a Eucharistic statement in June 2021 laying the groundwork for excommunicating pro-abortion Catholics, implicitly targeting prominent figures like Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi. We wrote about this development at the time with no small measure of glee.

To curb the defiance of American bishops, Pope Francis acted quickly, issuing the Motu Proprio3 “Traditionis Custodes” on July 16, 2021, which nullified Benedict XVI’s 2007 Motu Proprio “Summorum Pontificum”. This earlier decree had designated the Tridentine Mass, following the rite of Saint Pius V, as an “extraordinary” rite to ease its practice. In effect, Pope Francis’s Motus Proprio prohibited the Latin Mass, a tradition many American Catholics hold dear.

A papal election, despite the conclave’s seclusion, is a contentious political battleground with implications reaching well beyond Vatican walls. Since World War II, the United States, like it or not, has wielded considerable influence over these elections, often playing a critical role in determining their issue.

The Vatican is a linchpin for the United States in both foreign and domestic affairs. Catholics, numbering 70 million, form the nation’s largest organized religious bloc, historically maligned by WASPs. They are the only religious group expanding, fueled by Latino immigration and a rising tide of conversions from Protestantism, especially among the working and middle classes. Notable converts include Vice President JD Vance and Fox News anchor Laura Ingraham.

With its universities and vast network of schools—oftentimes the sole local affordable private alternative to America’s failing public education system—the U.S. Catholic Church commands formidable political clout. Today, its influence eclipses that of the WASPs, who, together with their American Jewish allies, have long shaped the nation’s political landscape.

The predominantly conservative American Catholic electorate poses a challenge for Democratic presidents like Barack Obama. It’s advantageous to support, if the opportunity arises, the election of a pope who can restrain the U.S. Catholic Church’s political and electoral influence.

This dynamic played out with Pope Francis’s election. Jorge Mario Bergoglio, a shrewd politician, consistently championed positions during his papacy that, while politically expedient, lacked broad support within the Catholic Church. Aligning with the agenda of his backers, he embraced issues like climate change and support for mass migration, resulting in a papacy that feels substanceless, even vacant. Bergoglio lacked the gravitas expected of a pontiff, who should rise above superficial societal debates. The Catholic Church is no NGO.

Jorge Mario Bergoglio embrassed the Davos-Obama archetype as pope, which accounts for the deliberate omission, post his 2013 election, of any scrutiny into his tenure as Argentina’s Jesuit provincial.

With Donald Trump’s second term ushering in a transformative shift, the next pope—emerging from what is expected to be a fiercely contested conclave—is likely to be conservative. This means he will recognize the Catholic Church’s civilizational significance, a perspective his predecessor sidestepped, not from a spirit of ecumenism but from calculated cynicism.

L’Humanité is a newspaper founded by Jean Jaurès before WWI. It later became the organ of the French Communist Party.

Banco Ambrosiano was an bank that was established in 1896 and collapsed in 1982. The Vatican’s Institute for the Works of Religion (IOR), commonly known as the Vatican Bank, was Banco Ambrosiano's main shareholder. The Vatican Bank was accused of funnelling covert United States funds to the Polish trade union Solidarity and to the Nicaraguan Contras through Banco Ambrosiano. Banco Ambrosiano and the IOR participated in mass money laundering for the Mafia.

In canonic law, a letter at the personal initiative of the Pope, tantamount to a decree or an instruction.