[ Analysis ] The Progressive Fourth Reich

Since 1919, Germany's political establishment has consistently worked to marginalize populists, with the notable exception of the NSDAP.

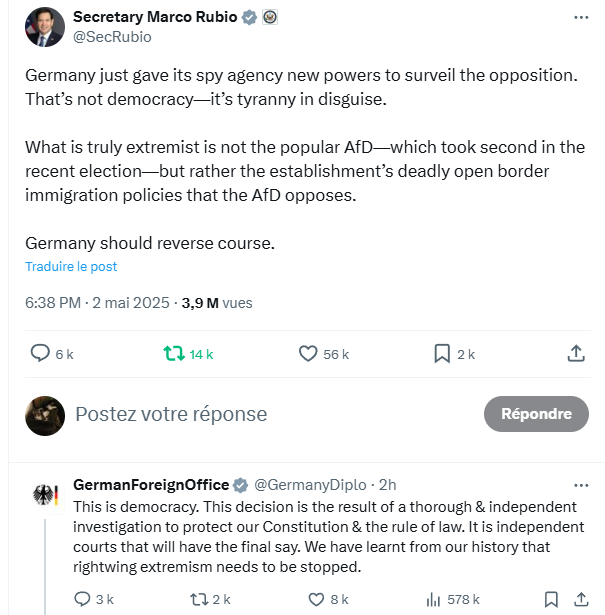

The German Foreign Ministry addressed U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s criticism of the decision to use domestic intelligence to monitor the AfD, officially deemed a far-right party and democratic threat. The ministry defended the move as consistent with democratic principles and grounded in an independent investigation upholding the rule of law.

The AfD’s nature—neither Nazi nor far-right—requires little scrutiny. It represents conservatives frustrated with Angela Merkel’s and the CDU-CSU’s policies. Its positions, including on immigration, might be tolerable, but its push for Germany to exit the Euro crosses an unacceptable line for the establishment.

The German domestic intelligence agency, the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV), operates under the Interior Ministry and is not independent. It serves the government, like all intelligence agencies. Its investigation into the AfD, is an administrative probe initiated by the Scholz government for political ends. The announcement came from the outgoing socialist Interior Minister, not the incoming minister of the anticipated Merz government, signaling entrenched political cartelization and the lack of backbone of the future chancellor.

The BfV’s 1,100-page report remains classified, with only select excerpts leaked to the press. The AfD is thus denied the ability to contest accusations, undermining any pretense of fairness.

Given the BfV's track record of botched cases—such as failing to stop the 9/11 planning in Hamburg, allowing most 2015 Paris terrorists to pass undetected through Germany, and unsuccessful attempts to ban Scientology and the far-right NPD party in court—along with questionable operations like the secret deal, revealed in 2015, it stroke with the NSA (exchanging German citizens' metadata for access to NSA's XKeyscore software), should the AfD be concerned ?

Claims of upholding democracy and the rule of law ring hollow when a political establishment that saw for the past 20 years to Germany’s decline, uses the state security apparatus to suppress the country’s main opposition and leading party (per polls).

The German political elite’s invocation of “learning history’s lessons” is misguided.

History shows Hitler was not democratically elected; the Nazi party always lacked a parliamentary majority. Appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933, by conservatives and liberals, Hitler organized elections promptly to strengthen his party’s government presence. The March 5, 1933, election, preceded by the Nazi-orchestrated Reichstag arson blamed on communists and a huge propaganda operation orchestrated by Goebbels and funded by industrialists, yielded only 43.7% for the NSDAP—no majority.

The Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich vom 24. März 1933, or Enabling Act for the Remedy of the Distress of People and Reich of March 24, 1933, was the law that eliminated the separation of powers, all held from now on by Adolf Hitler. Voted by each and every conservative and liberal members of Parliament, it effectively dismantled democratic checks, enabling the Nazis’ consolidation of power.

“We must acknowledge that the term Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act, editor’s note) is legally imprecise and even inaccurate. [...] The reality is that it is the temporary constitutional law of the new Germany,” noted Carl Schmitt1 at the time.

The key factor that facilitated the ascent of fascist and Nazi regimes in Italy and Germany is no longer present. Both Fascism and Nazism were aggressive, mass movements characterized by widespread, organized political violence. Major cities in Germany and Italy saw thousands of uniformed agitators dominating the streets. The decisive element was the street-level intimidation and coercion by paramilitary groups like the Blackshirts and the SA, which tipped the balance of power. Claims of a resurgence akin to the 1930s reflect a misunderstanding of historical realities.

Governing via decrees under temporary emergency laws was a recurring practice among Germany’s ruling elite. From 1919, Reich President Friedrich Ebert, a socialist, used this method to enact 116 laws in six years. Ebert also orchestrated the bloody suppression of the Spartacists, enabled by a secret 1919 pact with the military, revealed in 1924.

From 1930 and on, Reich President Paul von Hindenburg and Chancellors Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher routinized this practice, not for emergencies but to bypass parliamentary opposition and pass contested legislation, undermining democratic norms.

The EU’s use of Council regulations to enact measures like the Digital Services Act (DSA) mirrors this approach, shunting constitutional authority, which lies with Member States.

Germany’s political establishment—conservatives, liberals, socialists, and greens—has not absorbed the lessons of history. Suppressing popular demands, as seen in the lead-up to Nazism, risks radicalization. Nor has it learned from the German Democratic Republic’s Stasi, as their planned measures against the AfD—constant surveillance, infiltration, and administrative pressure—echo its tactics.

This approach, rooted in the worst of German political culture, has spread across Europe, particularly within EU institutions and among political elites. In France, for instance, President Emmanuel Macron transferred temporary emergency legislation enforced after the 2015 terrorists attacks into common law and used enabling laws in his first term to legislate by ordinance (e.g., on labor law). The frequent invocation of Article 49-32 by his governments to pass contentious acts, like pension reform via social security finance laws without debate, reflects similar methods. His refusal to acknowledge his constant national electoral setbacks since the 2022 general elections, which arguably warranted his resignation by July 2024 after losing the elections subsequent to his recall of the House, is another example.

It is ironic that Emmanuel Macron who has fully embraced Germany’s authoritarian ordoliberal model will, in October 2025, honor Marc Bloch3, the historian and author of L’Étrange Défaite, assassinated by the Gestapo in 1944, with pantheonization4.

In 1944, Bloch wrote in his diary: “The day will come, perhaps soon, when light will be shed on the intrigues in our country from 1933 to 1939, which favored the Rome-Berlin Axis, to hand over the domination of Europe to it, destroying with our own hands our alliances and friendships.”

Quoting Karl Marx nicely complements this: “Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.”

Carl Schmitt (1888–1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and philosopher known for his controversial contributions to legal and political thought, particularly in the context of constitutional law, sovereignty, and the nature of political power. Often labeled a conservative or reactionary thinker, Schmitt’s ideas have been both influential and divisive due to his association with the Nazi regime and his critique of liberal democracy.

After Cabinet deliberation, the French Prime Minister can tie the government’s responsibility to the passage of a finance or social security financing bill in the National Assembly. The bill is deemed passed unless a censure motion, filed within 24 hours, is voted. The government is then ousted. The Prime Minister may also apply this mechanism to one additional bill per parliamentary session.

Marc Bloch (1886–1944) was a prominent French historian, medievalist, and co-founder of the Annales School of historical research, which revolutionized historiography by emphasizing social, economic, and cultural history over traditional political narratives. Born in Lyon to a Jewish family, he served in World War I, earning the Legion of Honor for his bravery.

During World War II, Bloch joined the French Resistance against Nazi occupation. He wrote L’Étrange Défaite (Strange Defeat), a critical analysis of France’s 1940 defeat, attributing it to failures in leadership, society, and military strategy. Captured by the Gestapo, he was tortured and executed in 1944.

Bloch’s intellectual legacy and resistance heroism have made him a revered figure in France, culminating in his planned pantheonization in October 2025.

In France, pantheonization refers to the ceremonial act of transferring or commemorating an individual’s remains or legacy in the Panthéon in Paris, a monument dedicated to honoring distinguished French citizens. The Panthéon, originally built as a church for Saint Genevieve under Louis XV, was transformed during the French Revolution in 1791 into a secular mausoleum for “great men” (and later women) who embody French values, with the inscription: “Aux grands hommes, la Patrie reconnaissante” (“To great men, the grateful homeland”).