[ Flash ] Fine for X

The DSA is a hollow law—unenforceable in practice and useful only as a pressure tool. Its real function is to strong-arm platforms into censorship deals hammered out in backroom meetings.

Anyone still confused about what’s going on should read— or reread —the Twitter Files - France. The script is all there.

The DSA wasn’t some spontaneous burst of European regulatory virtue; it was drafted at the behest of the Obama administration back in 2016, crafted as a convenient offshore workaround to the First Amendment. Why muzzle Americans directly and unlawfully when you can outsource the job to the Brussels effect1 ?

Much worse: the “secret” deal that was struck with the Obama administration was to hand over on silver platter the personnal data of all European citizens (that’s the EU‑U.S. Privacy Shield of 2015, struck down by the EU Court of justice in 2020) in exchange for a licence to censor in Europe US plaforms to perserve the European establishment’s privileges, and to censor from Europe the American public so that the US establishment could keep its privileges. European leaders sold out European citizens, not even getting paid 30 silver coins in the process.

And the law’s rollout in February 2024—just seven months before the U.S. presidential election—surely must be another one of those remarkable coincidences. A pity, of course, that it came too late to influence the June 2024 European elections. Timing is everything.

What makes the whole performance even more theatrical is that EU member states have had perfectly adequate legal tools for removing illegal content since the 2000 e-commerce directive. In that light, the DSA looks less like a necessary regulation and more like a redundant instrument designed to give governments a shinier, more centralized lever over online speech.

The DSA is less a law than a bureaucratic contraption—an overbuilt, unworkable machine engineered to keep platforms permanently out of compliance. The point isn’t order; it’s leverage. If the rules are impossible to follow, then the authorities can extract whatever quiet censorship deals they want behind closed doors.

Take the saga of X.

June 2023: Brussels begins with an audit, declaring X’s moderation too soft on hate speech and disinformation—useful groundwork for what follows.

October 2023: The Commission escalates with a formal warning accusing X of fueling disinformation around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The message: fall in line.

June 2024: The Commission then floats a clandestine bargain—no fines, no public fuss, just censor what we tell you to censor, and everyone smiles for the cameras.

August 2024: Thierry Breton ups the ante, firing off a letter threatening Elon Musk with sanctions if he goes ahead with an interview featuring Donald Trump.

In the meantime, France’s under-secretary for European affairs, who owes his career to Washington (worked at the Hudson Institute and the Atlantic Council in DC), applauds. A prime target for the sanctions Secretary Rubio warned about?

The reasons for the fine against X are absurd.

Lack of transparency in its advertising registry? It’s disguised protectionism aimed at keeping the advertising market in the hands of the major agencies—Havas, Publicis, and the others. With platforms, there’s no longer any need to go through them for campaign design and media buying. Three months before the 2024 European elections, Havas, for example, was awarded a 123-million-euro framework contract by the European Commission for ad space purchasing, enough to keep just about every EU media outlet in line.

Refusal to give ‘researchers’ access to its internal data? This data is proprietary, and these ‘researchers,’ people like David Chavalarias, are not actually researchers but political activists seeking to impose algorithmic censorship aligned with their ideology.

The idea that the blue ‘verification’ badges are somehow deceptive is little more than a lawyerly quibble. On X, the blue badge isn’t a sacred seal of institutional authority—it’s a marker that the account holder pays for a subscription and is therefore tied to a verified payment method. In plain terms: this person exists.

To call that ‘misleading’ is to pretend the public can’t grasp the difference between identity verification and institutional endorsement. It’s a manufactured controversy built on semantic fog.

EU Commissioner Henna Virkkunen—described as both ‘ineffable’ and spectacularly out of her depth, especially after her much-criticized handling of Europeans’ personal data in Silicon Valley—insists that none of this qualifies as censorship. Her claim wilts under scrutiny.

The entire DSA mechanism is designed to coerce platforms into policing speech pre-emptively, not because judges have found anything illegal, but because the threat of ruinous fines hangs over them like a sword. It’s regulation by intimidation, not by law.

And here’s the irony: freedom of speech is the norm in all EU Countries. Any restriction must concern clearly unlawful content, proven with concrete evidence, and ordered by a court—not inferred, not hinted at, not nudged through bureaucratic or NGO pressure.

The Paris Judicial Court spelled this out plainly last September in the first two key DSA-related cases: censorship is the prerogative of judges, not bureaucrats, NGOs, corporations or individuals armed with vague threats and expansive interpretations of ‘compliance.’

The on-going legal offensive against X in France has all the hallmarks of political pressure dressed up as civic virtue.

Take Macronist MP Eric Bothorel’s complaint, having resulted in an ongoing . criminal investigation. He claims X suffers from a ‘reduction in the diversity of voices and perspectives,’ allegedly undermining its mission to provide a ‘safe and respectful environment for all.’

Conveniently omitted is any explanation of how a government-backed legal action to dictate what should be said on a platform is supposed to increase diversity of viewpoints. The circular logic would be comical if it weren’t wielded through the courts.

Bothorel also decries a ‘lack of transparency’ in algorithmic changes, along with Elon Musk’s hands-on management style, which he denounces as a ‘danger and threat to our democracies.’

And then there is the companion lawsuit, filed the very same day by a senior cybersecurity official, alleging that X’s algorithmic changes promoted ‘hateful, racist, anti-LGBT+ and homophobic’ political content ‘intended to distort democratic debate in France.’ This reads less like a neutral observation and more like a justification to place political speech under bureaucratic lock and key.

But we are meant to believe that none of this—neither the timing, nor the rhetoric, nor the coordinated court filings—constitutes an attempt to control the public conversation or to steer political discourse through judicial routes.

The choreography speaks for itself.

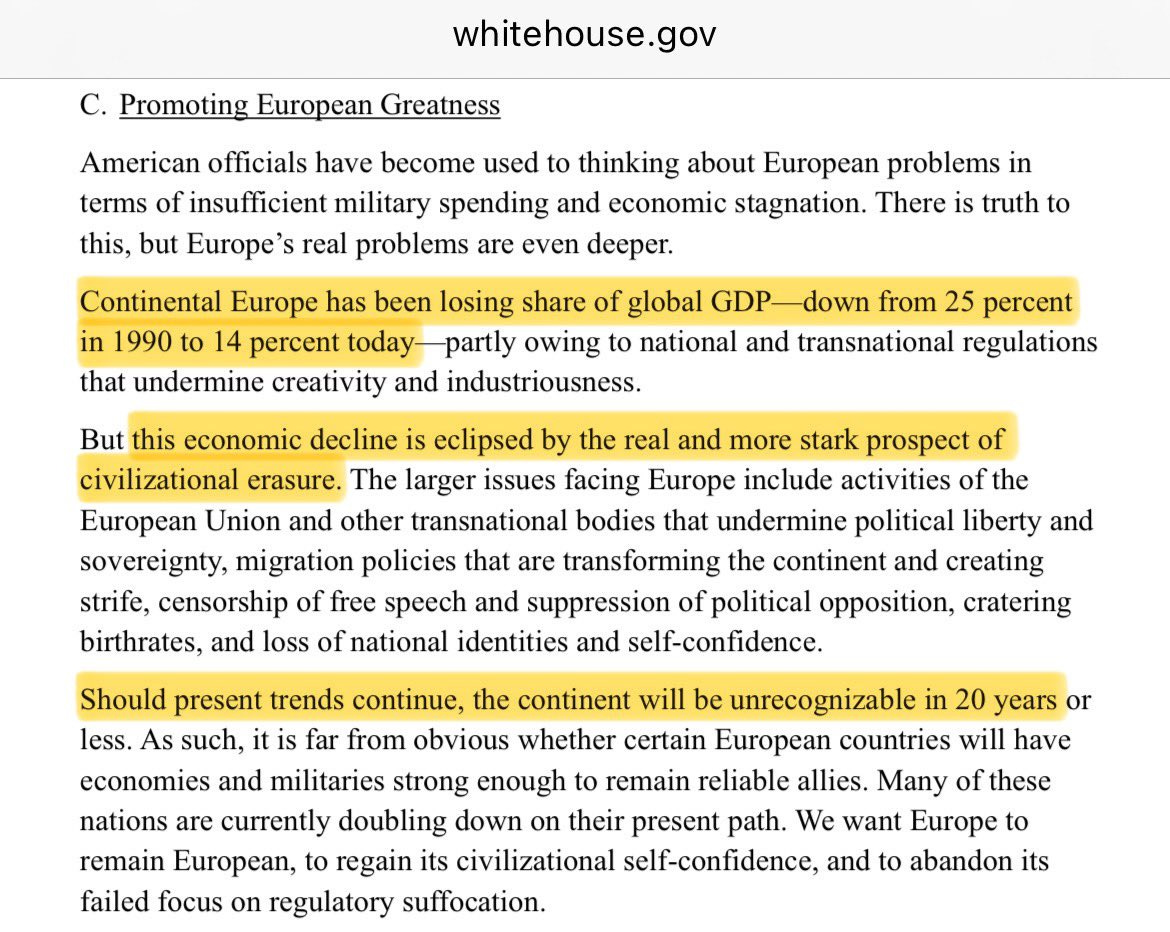

Finally, zoom out and look at this episode through the lens of the new U.S. national security strategy. In that document, the message is spelled out with brutal clarity: Europe, increasingly willing to sidestep core democratic principles like freedom of expression, can no longer be considered a reliable American ally.

In other words, Washington now openly questions whether Brussels still belongs to the club of liberal democracies it claims to champion. It’s a remarkable reversal: Europe, self-styled guardian of human rights, being graded down by the very country that once looked to it as a model. The geopolitical subtext is unmistakable—and deeply embarrassing for those insisting the DSA is merely harmless content moderation.

Behold today’s European establishment, many of whom owe their elevated seats to the favor of U.S. Democrats and the ever-shadowy machinery of Washington’s permanent bureaucracy. And now they shriek in outrage, as if the heavens themselves were collapsing, the moment someone questions their authority or disrupts the script they’ve grown accustomed to reciting.

The spectacle has the flavor of a political opera: grandees who rose with outside backing now performing indignation at full volume, hoping no one notices who tuned their instruments in the first place.

The Brussels effect is the fact that regulating a market the size of EU tends to impose European norms globally.