GrapheneOS : Beyond the Data

Part Two. The Addiction to data as “judicial evidence.” Two American experts weigh in—because apparently nothing says justice like drowning in terabytes.

In the first part, we exposed what GrapheneOS actually is—and why this free, open-source operating system gives the State such a headache. Whether officials truly don’t understand it or simply find it convenient to play dumb, the result is the same: a bureaucracy flailing in the dark and blaming the flashlight.

In this second part, you’ll see that ChatControl—the European fever dream that would scan every message before it’s even encrypted—was never about fighting child abuse. That’s the sales pitch. The real goal is to slip in a continent-wide mass-surveillance machine, the kind the EU’s own Court of Justice has already said is illegal. And as if that weren’t enough, Europol is demanding backdoors to remotely access every device, because nothing says “trust us” like asking for a skeleton key to everyone’s digital life.

Of public interest, the article is free.

Let’s have a bit of fun. DSA, paragraph 20:

Where a provider of intermediary services deliberately collaborates with a recipient of the services in order to undertake illegal activities, the services should not be deemed to have been provided neutrally and the provider should therefore not be able to benefit from the exemptions from liability provided for in this Regulation. This should be the case, for instance, where the provider offers its service with the main purpose of facilitating illegal activities, for example by making explicit that its purpose is to facilitate illegal activities or that its services are suited for that purpose. The fact alone that a service offers encrypted transmissions or any other system that makes the identification of the user impossible should not in itself qualify as facilitating illegal activities.

France, pursuant the DSA, has no case against GrapheneOS.

The State’s latest excuse for taking another swing at privacy—this time by going after GrapheneOS—is, predictably, drug trafficking. Supposedly, accessing someone’s phone is now the magic key to every major criminal investigation, especially those involving organized crime.

Europe’s obsession with hoarding data traces back to two big cases—and one spectacular FBI sting operation.

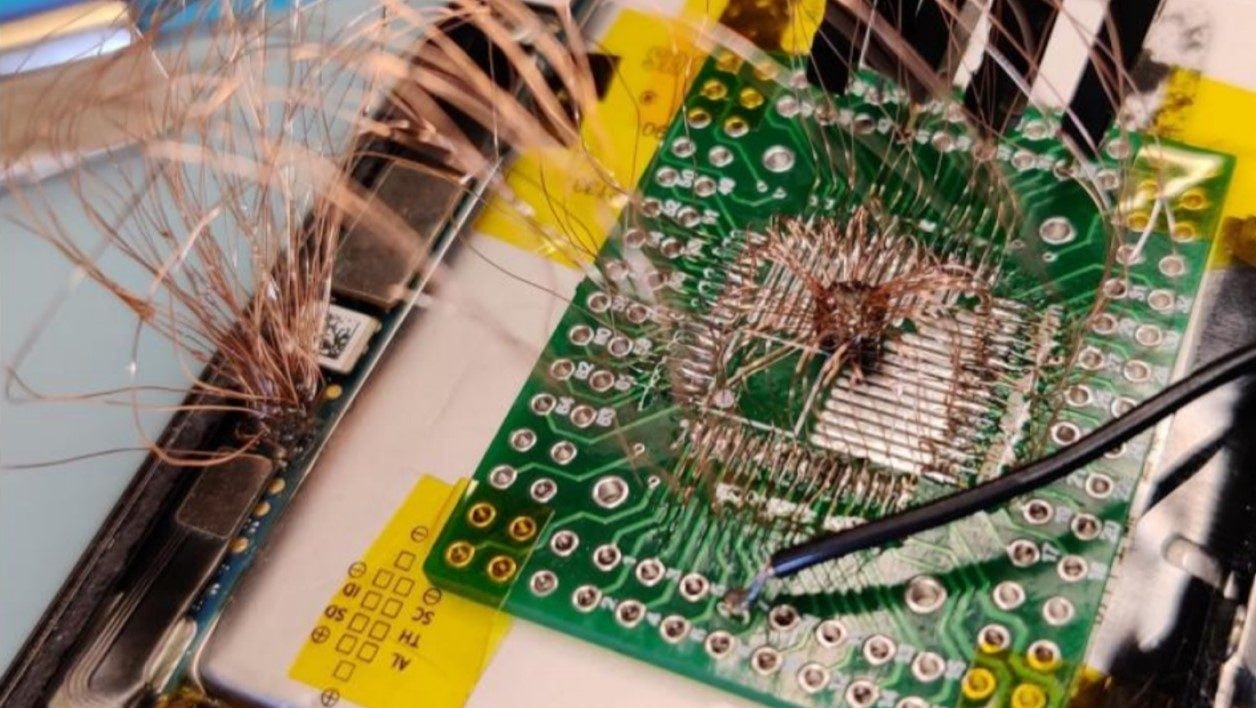

The first? Encrochat, a Dutch company that sold encrypted communications on heavily modified phones—cameras disabled, GPS dead, microphones killed, sensors neutered, plus a “secret” Android overlay. It was a closed network: only Encrochat-modified phones with paid subscriptions could talk to each other. Messages didn’t touch the phone network; everything ran through Encrochat’s servers—housed, of all places, in France, at OVH in Roubaix.

After Dutch police stumbled on these devices in 2017 during raids on the “Mocromafia,” French gendarmes1 managed in 2020 to infiltrate Encrochat’s servers. They pushed out malware capable of sucking up location data (when enabled), passwords, messages, and the Wi-Fi access points the phones were using. You’ll see later why hoovering up all that data matters. The result? Hundreds of arrests, tons of drugs seized, tens of millions of euros frozen, and enough weaponry to equip a small militia.

The second case: Sky ECC, from Canada’s Sky Global. Same idea, different platform—this time Blackberry. Again: server infiltration, mass data siphoning, and bulk arrests in Belgium and the Netherlands.

And then comes the FBI with its pièce de résistance. After Encrochat and Sky ECC imploded, the Bureau had a bright idea: design and distribute its own criminal “secure phone” through an informant. The market vacuum did the rest. This was Trojan Shield / ANOM, a global honeypot. The tally? Over 800 arrests across sixteen countries—except in the U.S., where the very evidence harvested is inadmissible thanks to laws that—ironically—protect privacy.

Behind these supposedly clean, efficient operations lie uncomfortable questions, starting with their legality.

In the UK, evidence from Encrochat got tossed because prosecutors couldn’t prove who actually sent the messages. That’s the recurring nightmare of electronic evidence: you must first prove identity to attribute content.

Hence the French malware. Those extra data points create enough technical breadcrumbs to strongly infer who owned and/or used a device. Strongly infer, not prove.

The biggest legal landmine: indiscriminate, mass interception of all communications from all users of a service using intrusive methods. Under EU law, that’s flat-out illegal. Intrusions must be targeted, justified, and judge-authorized. Anything collected otherwise is toxic waste—unusable in court.

That applies to Signal, WhatsApp, Telegram, or France’s most widely used app by criminals, Snapchat. Since Emmanuel Macron handed French citizenship to CEO Evan Spiegel as a royal favor, one imagines his cooperation is expected—if only to avoid the treatment inflicted to Telegram’s Pavel Durov.

Across continental Europe, defense lawyers filed mass motions to purge Encrochat evidence. No luck. French and German high courts both declared the collection lawful.

Justifying this legal contortion? By claiming that Encrochat, Sky ECC, and ANOM existed for criminal organizations, and that nearly all users were criminals anyway—because the tools were supposedly “built for crime.”

But here’s the catch: Encrochat, Sky ECC, and Anom were closed proprietary networks. GrapheneOS is not. It’s not a communications service, not a secure messenger—it’s an open-source operating system, downloadable for free. It runs only update servers. It only enables to evade private mass surveillance by Google and app developers. That’s it.

Drug cartel bosses aren’t idiots. They learn. They realized specialized “crime phones” paint a giant target on their backs. So they blend into the crowd—using mainstream apps.

And on Signal, WhatsApp, Telegram, Snapchat? Mass interception is illegal. Meaning: no more desk-chair investigations producing flashy headlines for political PR. Investigators once again have to do the hard stuff: real surveillance, real intelligence work, real field investigations.

This, most likely, is why governments have fixated on phone access—and why France is trying to smear GrapheneOS as an Encrochat clone. Their Israeli gadgets - Cellebrite e.g. - aren’t working, so GrapheneOS becomes the scapegoat.

Some will say: “If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.” Sure. But the State has no right to rummage through your life unless a judge signs off. This isn’t a suggestion—it’s a fundamental human right.

Far be it from us to demean French police investigators. But since Sarkozy’s “results-orientated policing” and especially under Macron, pressure on judicial police forces has surged to unbearable levels.

The more the government fails to maintain order—through incompetence, spinelessness, or intentional laxity—the more it needs spectacular headline-grabbing busts to maintain the illusion of control.

So we looked at the U.S.—the pioneer of organized crime enforcement—to see how they handle electronic evidence.

We spoke anonymously with two experts with extensive experience fighting organized crime, especially narcotics. Here’s what they told us.

GrapheneOS is a non-issue in the U.S. because the Fifth Amendment protects against self-incrimination. No one can be forced to give up their phone unlock code. Period.

GrapheneOS devices behave like any others on telecom networks. Cell tower data is usually far more useful than what’s inside the phone. GrapheneOS only protects against private mass surveillance—Google, app vendors—not criminal investigations.

If police seize a phone during a search, it’s on the State to unlock it. And yes, they use tricks—for example, grabbing the phone right after the suspect unlocks it to call a lawyer.

The experts confirmed smartphones can be a goldmine—mostly in “general criminality” and street crime, like gangs. Their favorite example: the wife scheming with her lover to murder her husband over an encrypted chat, forgetting to enable disappearing messages and oblivious that server data can be subpoenaed.

But when it comes to real organized crime—professionals, not street thugs—the value of phone data plummets.

These people are disciplined. They know phones are liabilities. They don’t stop communicating, but they make sure messages can’t be tied to them. Content is worthless if identity can’t be proven.

They use burner phones bought with cash. They keep “personal” and “business” phones separate, with the latter wiped clean. They rotate SIM cards, muddying both line attribution and location tracking. And they always have a plan to ditch devices instantly.

In Europe, Encrochat/Sky ECC users thought they were sophisticated. They weren’t. They were sending encrypted proofs of their own crimes. These people had no operational security whatsoever.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., drug cartels—mostly from Latin America—are structured, compartmentalized operations. Each member communicates only with the necessary few. They’ve run their own communications infrastructure for decades. Colombian cartels in the 70s and 80s were already using secure HF radios to coordinate cocaine shipments to Florida.

In organized crime, phones yield little evidence—but lots of useful intelligence. ANOM produced no prosecutions in the U.S. because the evidence was inadmissible. But the intel accelerated investigations and opened new ones.

Real organized crime cases rely on a layered approach: physical surveillance, wiretaps, undercover infiltration, and especially confidential informants. Only this combination builds the kind of airtight case required under RICO to take down entire organizations—including their insulated bosses.

These cases take time to build—two to five years on average.

Organized crime is either illicit commerce (products flowing one way, money flowing back another separate way) or illicit services (e.g., sexual exploitation for cash). Targeting revenue is often more effective than going after goods, which is primarily customs’ job when it comes to narcotics.

No one in organized crime closes major deals with strangers. Big moves require in-person meetings. Hence the central role of traditional police work and international cooperation.

The U.S. has two major advantages over Europe:

An uncompromising justice system with extremely heavy federal sentences. This makes flipping informants easier: reduced sentences in exchange for intel or testimony. “Three strikes”—25-to-life on the third major offense—breaks even hardened criminals.

Undercover infiltration is legal without judicial oversight, even when designed to provoke crime.

What does all this tell us?

Electronic evidence pulled from phones is messy. Its admissibility depends on attrubtion, extraction methods, forensic tool credibility, metadata integrity, and the risk of alteration during extraction. Experts fight endless battles over it. It never replaces solid physical evidence—it only supplements it.

For intelligence, phone data is useful—but in the U.S. it cannot be collected in ways that violate privacy or sidestep judicial oversight, unlike the free-for-all that has become alarmingly common in continental Europe, especially in France.

The French Gendarmerie Nationale, a law enforcement agency under military status, has Europe’s best cybercrime and data forensics unit.

Sharp analysis of the ANOM honeypot and how it exposed the operational security gap in supposedly secure networks. The contrast between Encrochat users leaving digital breadcrumbs everywhere versus real organized crime staying disciplined is critical. Attribution remaints the weak link in electronic evidence, and bulk collection creates legal landmines taht most jurisdictions cant navigate cleanly. Smart breakdown.